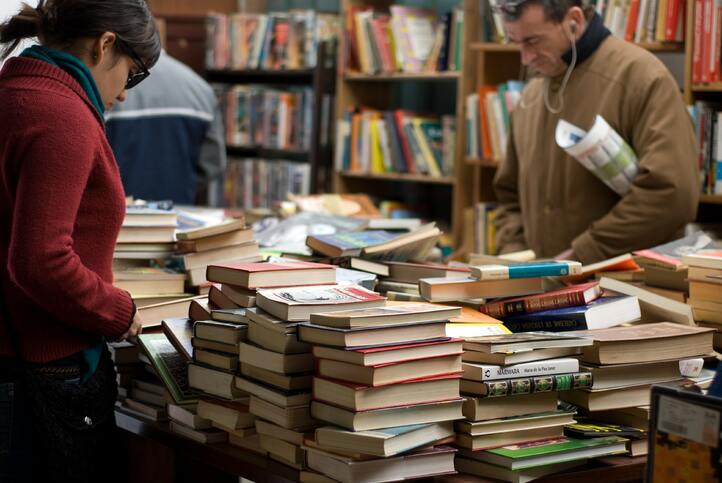

The resistant book in the middle of the Rastro

The Juanito bookstore survives, after three generations, pandemics and technological avalanches.

On the ceiling hangs a Canadian Inuit kayak that he rescued from a colonial-style bar that closed its doors. In the background an oriental gong whose long vibration floods the entire room and transports you to places even more exotic than the Rastro in Madrid, if possible. Juan Ruiz (Madrid, 46 years old), owner of the Juanito bookstore, also traded in antique objects, but now he focuses on books, which is what he does best. "An antique store is a very nice thing, but a difficult business, many are closing," he says. His is one of the Madrid establishments that, in one way or another, survives the multiple crises of 2020, while others , such as the veteran stationery store Salazar or the Café de Chinitas, have had to close.

Ruiz grew up in the streets of the neighborhood, in the 80s, playing soccer, dribbling heroin syringes in the square, watching the characters of the Movida madrileña. "I was little, but I was perfectly aware of the Movida: we kids were very attracted to the punks with colorful crests. There was an incredible atmosphere, in bars like the Bobia or the Diamante," he recalls. But what he remembers most is the drugs: "There were a lot of people lying around in doorways.

He is the third generation to run this bookstore at number 8, Plaza del General Vara del Rey. While his grandfather Juanito, who started at the end of the 1960s, and his father José Luis, were dedicated to antiquarian books, Juan has successfully introduced the more modern second-hand book: on his shelves and shelves you can even find novelties, but practically at half price. "Of course, I get a lot of bargaining," says Ruiz, "you have to be patient.

As the business happens mostly on Saturdays and Sundays at the Rastro, he spends a good part of the week chasing tips and visiting private homes, buying books and entire libraries. "Whenever they call me, I go: sometimes they tell you wonders and what you find is worthless; other times they don't give me many expectations and I find exceptional things," explains Ruiz. And precisely as the business happens on Saturdays and Sundays of Rastro, the covid pandemic that has left the Madrid market inactive for months has also affected him strongly: in 2020 he has entered just half that in 2019, which, curiously, was his best year.

Surveys say that the confinements have revived the love of reading, "although I believe," says the bookseller, "that those who did not have a reading habit before are not going to get into it now." It is also said that many bookstores have weathered the crisis well, but Ruiz has noticed it, precisely because of their dependence on the weekend strolling masses. "If there is any place where there are crowds, it is at the Rastro, so I understand perfectly well why it has been closed for so long," he says, "I would also understand if they forced me to close again if things got really bad".

On the wall hangs a photo of him chatting at the door of the bookstore with the writer Andrés Trapiello (who has just published his book Madrid en Destino). "He is one of the people who has done the most to promote the Rastro," says the bookseller. The other day a feral photographer showed up and stole a photo of them. A week later he showed up again: "I'm the one who took your photo," he said, and gave him a printed copy. It is displayed next to a poster that says: "Smart kids read books".

Juan Ruiz took the reins of the establishment in the wake of the 2008 crisis: he lost his job in the tourism sector and took refuge in the family business. Then he did better and better, until he reached that peak of profits in 2019. And then this collapse. Now, with this new crisis that seems to dwarf that one, the business is a lifeline. "I'm going through some tight spots, but I'm going to hold on," he predicts. For this he has a secret weapon: he owns the premises, which his grandfather bought when it was a paint shop. "Many of the businesses that are closing around here have this common characteristic: they have to pay rent," observes the bookseller, for whom it is also important to lead an austere life: he has no children, no partner, and no big car. "I believe that the real threat to reading is not the crises, but the new technologies: the smartphone, the tablet, digital platforms. Nobody reads on the subway anymore," he laments.

El Rastro has changed a lot since his childhood. "I think it has been adapting to the new times and has lost its personality. Because the new times have no personality."